The laboratory notebook sits open on the conference table. One line, written in blue ink six months ago, will determine whether your patent survives or dies. That line contains a temperature range—180 to 200 degrees Celsius—suggested by a graduate student who left the company last week.

If that temperature range appears in any of your patent claims, the graduate student is an inventor. Not a contributor. Not an assistant. An inventor with equal rights to the professor who conceived the core technology.

U.S. patent law recognizes only one test for determining inventorship: conception. The person who mentally forms the complete technical solution becomes the inventor. The team that spends months building prototypes? They’re not inventors unless they conceived claimed elements. The CEO who funded everything? Not an inventor without technical conception. The technician who suggested one critical parameter? Full joint inventor if that parameter appears in claims.

This brutal clarity creates a minefield. Patents worth millions can become unenforceable when the wrong names appear—or don’t appear—on the first page¹. Courts invalidate patents for incorrect inventorship. Companies lose enforcement rights. Omitted inventors surface years later demanding ownership shares.

This guide provides the framework for proper inventorship determination: systematic claim-by-claim inventorship analysis, documentation that survives litigation scrutiny, and correction procedures that preserve patent validity when errors surface.

Key Takeaways

- Inventorship requires conception, not execution: Only those who mentally form the complete technical solution qualify as inventors—building, testing, or funding alone creates no inventorship rights.

- The conception standard is definitive: An inventor must have “a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention” that someone skilled in the art could practice without extensive research¹.

- Joint inventorship is all-or-nothing: Contributing to even one claim makes you a joint inventor of the entire patent with equal rights².

- Incorrect inventorship can be fatal: Patents become unenforceable without proper inventorship, though correction is possible if no deceptive intent exists³.

- Documentation timing matters: Conception must be recorded when it happens—reconstruction after disputes rarely survives litigation.

- Claim language controls everything: Inventorship determination requires comparing each conceived element against every patent claim.

The Buffer Solution Story

The following scenario illustrates how inventorship errors can destroy patent value:

March 15, 2019. A Tuesday morning lab meeting at a biotechnology startup.

The senior scientist draws molecular structures on the whiteboard, explaining the enzyme modification that could revolutionize drug delivery. The post-docs nod, taking notes. A laboratory technician raises her hand.

“What if we try phosphate buffer at 0.5 molar instead of 0.1? Might stabilize better at low pH.”

“Worth a shot,” the senior scientist says, adding it to the experiment list.

Six months later, the optimized enzyme enters clinical trials. The buffer concentration—exactly 0.5 molar—appears in claim 17 of the patent application. The technician’s name appears nowhere.

Two years pass. The technician, now working elsewhere, reads about the company’s substantial valuation. She hires a lawyer. The lawyer reads claim 17.

The Federal Circuit’s precedent is clear: conceiving the buffer concentration equals conceiving claim 17. Conceiving any claim creates joint inventorship of the entire patent. The company’s failure to name her constitutes incorrect inventorship. If deceptive intent is found, the patent family—six related patents covering the core technology—could become unenforceable.

The acquisition collapses. Emergency sale at a fraction of the original valuation. Shareholders sue. The senior scientist’s career implodes.

One suggestion. One claim element. One unnamed inventor. Everything lost.

Who Qualifies as a Patent Inventor? The Only Test That Matters

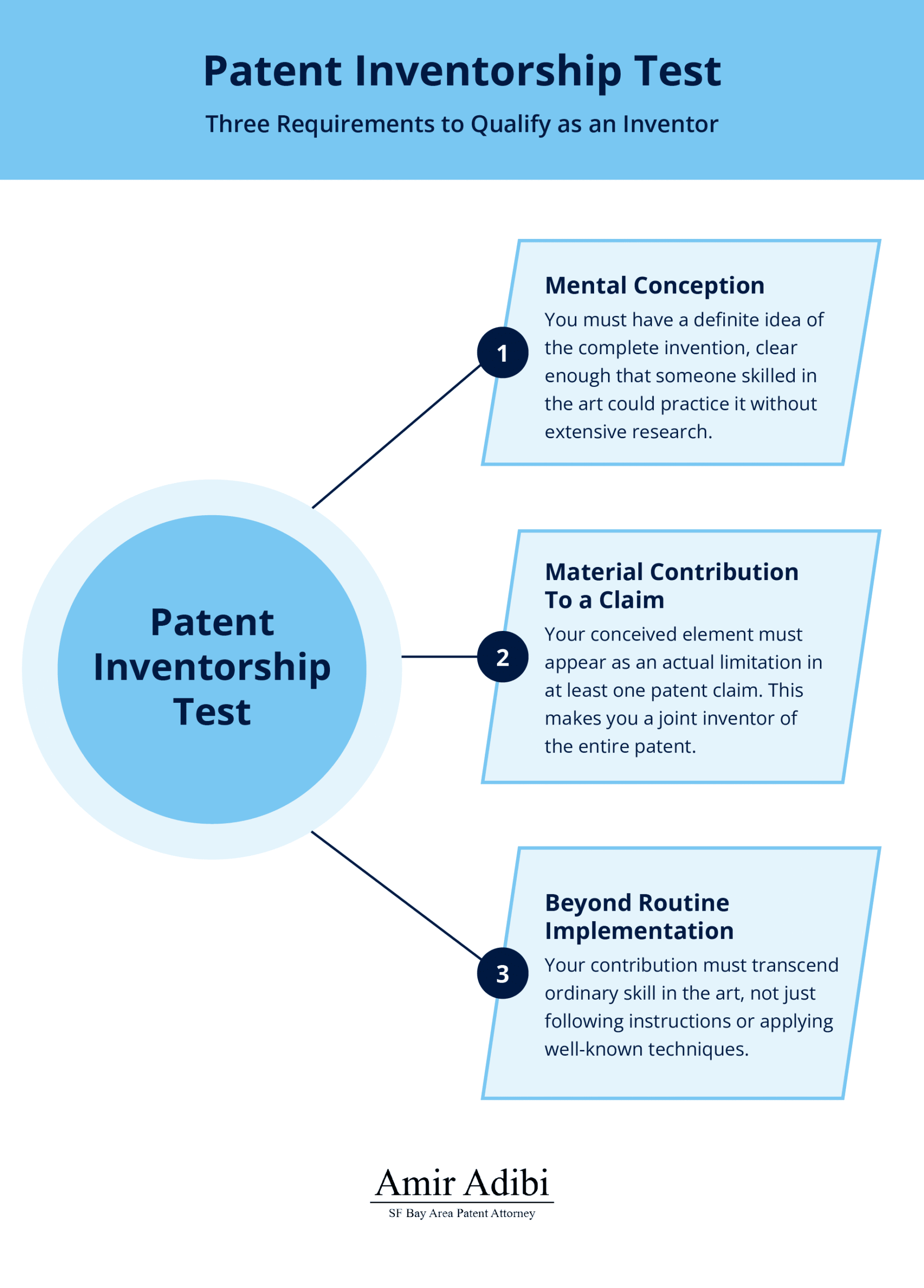

Forget what seems fair. Forget who contributed most. Forget who took the risk or paid the bills. Patent inventorship requirements follow three unforgiving rules:

- Mental conception of the complete solution – The invention must fully form in your mind, detailed enough for someone skilled in the field to build it without extensive experimentation.

- Material contribution to at least one claim – Your conceived element must appear as an actual limitation in at least one patent claim.

- More than routine implementation – Your contribution must transcend ordinary skill in the art.

The critical insight: conception vs reduction to practice determines everything. The moment you mentally picture the complete technical solution, you become an inventor. Everything that follows—prototyping, testing, optimizing—creates no inventorship rights unless it produces new conceived elements that appear in claims.

This paradox destroys companies: The graduate student who suggests one temperature range becomes an equal owner with the professor who conceived the fundamental breakthrough. Contribute to claim 20 out of 20? You own the same rights as whoever conceived claims 1 through 19.

Smart organizations map patent inventorship requirements systematically before filing patents, not after disputes explode. For complex scenarios with unclear contribution boundaries or multi-party research teams, patent consulting services provide critical analysis before positions crystallize into conflicts.

Legal Framework for Determining Inventorship

The Conception Standard: When Invention Happens

The laboratory buzzes with activity. Centrifuges spin. Researchers peer at data. Somewhere in this chaos, an invention occurs—not when the experiment succeeds, but when someone’s mind forms the complete solution.

Legal Definition of Conception: “The test for conception is whether the inventor had an idea that was definite and permanent enough that one skilled in the art could understand the invention.”¹

Patent law draws a sharp line between thinking and doing. Conception creates inventors. Reduction to practice creates nothing.

The Divide That Determines Everything

| Conception | Reduction to Practice |

| Complete mental picture forms | Months of building and testing |

| Happens in seconds | Unfolds over months or years |

| Cannot be delegated | Often assigned to others |

| Creates permanent rights | Creates only working prototypes |

| Needs only clarity | Needs actual functionality |

| Proven by dated records | Proven by test results |

Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Laboratories (1994) crystallized this standard¹. The Federal Circuit ruled conception completes when “the inventor has a definite and permanent idea allowing one skilled in the art to practice the invention without extensive research.”

You don’t need proof it works. You don’t need a prototype. You need only that flash of complete understanding.

When Ideas Become Inventions

Professor Chen stares at the efficiency problem in solar cells. Traditional materials waste too much light. Then it clicks: quantum dots, but specifically 3 to 5 nanometers. That size will capture the right wavelengths.

Graduate student Martinez takes Chen’s idea to the lab. Six months of temperature variations. Hundreds of synthesis attempts. Finally discovers that 180-200°C produces perfect 3-5 nm dots consistently.

If the patent claims recite: “quantum dots having a diameter of 3-5 nm” Chen invented it alone. Martinez built what Chen conceived.

But if any claim recites: “quantum dots synthesized at a temperature of 180-200°C” Chen and Martinez co-invented it. Martinez conceived the temperature range.

Fina Oil v. Ewen (1997) delivered the shocking corollary: “[A] joint invention is simply the product of a collaboration between two or more persons working together to solve the problem addressed”². Contributing to just one claim—even the narrowest dependent claim—makes you a joint inventor of the entire patent. No proportional ownership based on contribution size. Binary: inventor or not.

The timing of conception matters. What seems novel today might be obvious tomorrow. Patent search services establish the prior art landscape at conception time, distinguishing genuine invention from mere application of known principles.

35 U.S.C. § 116: How Joint Inventorship Works

Congress rewrote inventorship law in 1984, acknowledging how research happens⁴:

“Inventors may apply for a patent jointly even though (1) they did not physically work together or at the same time, (2) each did not make the same type or amount of contribution, or (3) each did not make a contribution to the subject matter of every claim.”

Translation: Joint inventors don’t need to know each other, work together, or contribute equally. They need to conceive claimed elements.

Three Key Court Decisions

Eli Lilly v. Aradigm (2004) – A researcher conducts months of experiments confirming the invention works exactly as predicted. The Federal Circuit established that “there is no explicit lower limit on the quantum or quality of inventive contribution required for a person to qualify as a joint inventor”⁵—but testing alone, without conception, creates no inventorship rights.

Stern v. Trustees of Columbia (2006) – Columbia University argues their researcher’s “significant overall contribution” should establish inventorship. The Federal Circuit clarified that “conception is the formulation in the mind of the inventor, of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention”⁶—only contributions to specific claimed elements matter.

Dana-Farber v. Ono (2020) – Two scientists provide tumor models essential to developing the invention. Without their protocols, no success. The Federal Circuit ruled: “The inventorship of a complex invention may depend on partial contributions to conception over time”⁷—but critical assistance alone isn’t conception.

The Three-Question Test

Every potential inventor faces three requirements:

- Did you conceive, or merely execute?

- Was your contribution more than trivial?

- Does your contribution appear in claims?

Unless all three get a “yes,” you’re not an inventor—regardless of hours worked, risks taken, or value created.

Conception vs. Reduction to Practice: The Critical Distinction

A researcher stands at the whiteboard, sketching molecular structures. She modifies a side chain, adds a fluorine atom at position 6, creating a theoretical compound that should penetrate the blood-brain barrier 10 times better than existing drugs.

Has she invented it? Yes—if the structure she drew appears in patent claims.

Her colleague spends the next year synthesizing the molecule. Twelve failed attempts. Different reagents. Temperature adjustments. Finally, success—the exact molecule the first researcher drew.

Has the second researcher invented anything? No—unless the synthesis method appears in claims.

This feels wrong. The person who made it real gets nothing while the person who imagined it owns everything. But patent law rewards mental breakthroughs, not physical implementation.

The Time Paradox

Invention happens in milliseconds—the instant conception crystallizes. An MIT professor conceives a quantum computing breakthrough during a conference coffee break. The graduate student who spends three years building it in the lab? Not an inventor unless they conceive improvements that appear in claims.

Conception Timing Illustrated

| Event | Date | Inventorship Impact |

| Professor sketches core algorithm | March 1, 9:47 AM | Becomes inventor |

| Funding secured | March 15 | No impact |

| Team assembled | April 1 | No impact |

| Student suggests error correction | June 3, 2:15 PM | Becomes co-inventor if claimed |

| First prototype built | December 1 | No impact |

| Patent filed | December 15 | Inventorship locked |

The March 1 sketch and June 3 suggestion—moments of conception—created all inventorship rights. The months of work between? Legally irrelevant unless they produced new conceived elements.

Determining Inventorship: A Systematic Approach

Step 1: Identify All Conceived Elements

List every technical contribution, however minor:

- Core concepts

- Specific parameters (temperatures, pressures, concentrations)

- Process steps

- Structural features

- Performance characteristics

Step 2: Map Contributions to Claims

Create a contribution matrix:

| Contributor | Conceived Element | Appears in Claim # | Inventor? |

| Dr. Smith | Polymer backbone | 1, 5, 12 | Yes |

| J. Johnson | Crosslinking temp (180°C) | 3 | Yes |

| K. Davis | Mixing protocol | Not claimed | No |

| L. Chen | Characterization method | Not claimed | No |

Step 3: Apply the Conception Test

For each contribution, ask:

- Was it complete enough for skilled implementation?

- Did it require inventive insight beyond routine skill?

- Does the exact element appear in at least one claim?

A “no” to any question eliminates inventorship for that contribution.

Common Misconceptions That Create Legal Disasters

“The PI is always the inventor” Principal investigators who manage but don’t conceive claimed elements? Not inventors. The Federal Circuit consistently rejects “supervisory inventorship.”

“Everyone on the paper should be on the patent” Authorship recognizes all contributions. Inventorship requires conception of claimed elements. Most authors aren’t inventors.

“We’ll figure it out if the patent becomes valuable” Inventorship disputes years later face faded memories, lost documents, and conflicting stories. Courts favor contemporaneous evidence—if it exists.

“Small contributions don’t count” Conceive one temperature range in one dependent claim? Full joint inventor with equal rights to the entire patent.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

Patent litigation costs average $1.6 million through discovery and $2.8 million through final disposition according to the American Intellectual Property Law Association⁸. With 95-97% of patent lawsuits ending in settlement⁹, the financial impact of inventorship disputes extends far beyond legal fees.

Immediate Costs

Certificate of Correction: $160 USPTO fee¹⁰ plus attorney time ($2,000-5,000)

Reissue Application: $2,000-10,000 in attorney fees plus USPTO fees

Pre-Litigation Settlement: $50,000-500,000 depending on patent value

Long-Term Consequences

The median damages awarded in patent litigation cases have ranged from $1.9 million to $17.4 million⁹, often exceeding the patent’s actual value when inventorship disputes trigger broader challenges to validity and enforceability.

Claim-by-Claim Inventorship Analysis

The patent attorney spreads twenty pages across the conference table. Each page contains one claim. She places a colored sticky note on each: green for Dr. Anderson, blue for Dr. Zhang, yellow for both.

“Claim 1 recites the base polymer structure—that’s Anderson’s conception from the January notebook entry.”

Green sticky.

“Claim 2 adds ‘wherein the polymer has a molecular weight of 50,000 to 75,000 Daltons.’ Who conceived that range?”

The team reviews notebooks. Zhang’s April entry: “MW should be 50-75k for optimal viscosity.”

Yellow sticky—both are co-inventors.

“Claim 3 adds the crosslinking temperature. The draft says 150-200°C. Who determined that?”

Anderson checks her notes: “I wrote ‘high-temp crosslinking’ but never specified the range.”

The manufacturing engineer speaks up: “I ran the temperature studies and found 150-200°C optimal.”

The attorney pauses. “Did you conceive that range as necessary for the invention to work?”

“Yes, below 150 wouldn’t crosslink properly. Above 200 degraded the polymer.”

Blue sticky for the engineer—now a co-inventor of the entire patent.

The Surgical Precision Required

Each claim element demands analysis:

Independent Claims: Establish base inventorship

- Who conceived each limitation?

- Does prior art impact who contributed novel elements?

- Are all elements actually novel, or are some admitted prior art?

Dependent Claims: Can add inventors

- New limitations = potential new inventors

- Narrowing limitations still count

- Even trivial-seeming additions matter if they required conception

Documentation That Survives Litigation

The lab notebook page is dated, signed, and witnessed. The conception is described clearly: “Realized that adding 2-5% glycerol would prevent crystallization during storage.”

Three elements make this bulletproof:

- Contemporaneous – Written when conceived, not reconstructed later

- Specific – Exact parameter (2-5% glycerol) not vague concept

- Corroborated – Witnessed signature provides independent verification

The inventor sketching on a napkin? Photograph it. Date it. Have someone sign as witness. The Slack message suggesting a parameter? Screenshot with timestamp. The video call where conception occurs? Record it (with consent) and transcribe the key moment.

Common Inventorship Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

The Courtesy Inventor Trap

The CEO wants his name on every patent. The department chair expects inclusion. The major investor “contributed strategic vision.”

None of them conceived claimed elements. Adding them anyway? You’ve just handed future opponents a weapon. Incorrect inventorship with deceptive intent can invalidate entire patent families. Courts show no mercy for “honorary inventorship.”

Safe Harbor Protocol: Create a written policy that inventorship follows legal requirements, not corporate hierarchy. Have executives acknowledge this in writing before R&D begins.

The Forgotten Contributor Problem

The summer intern who suggested the catalyst temperature. The consultant who proposed the circuit design. The former employee who conceived the core algorithm.

Missing inventors surface years later, often after the patent becomes valuable. They demand correction, ownership shares, or both. Their leverage? The threat of rendering the patent unenforceable.

Prevention Checklist:

- Exit interviews specifically asking about patent contributions

- Invention disclosure forms signed by all technical staff

- Consultant agreements addressing inventorship explicitly

- Regular inventorship reviews as claims evolve

Multi-Party Research Collaborations

University partners with industry. Three companies form a joint venture. Government lab collaborates with startup.

Each organization has different policies, different goals, and different understanding of inventorship. The result? Disputes that destroy partnerships and patents simultaneously.

Collaboration Framework:

| Element | Must Include |

| Contribution Tracking | Real-time documentation system all parties use |

| Inventorship Determination | Specified procedure and decision authority |

| Dispute Resolution | Binding arbitration clause with technical arbitrator |

| Correction Procedures | Pre-agreed process if inventorship changes |

| Ownership Separate from Inventorship | Clear that employment/funding doesn’t determine inventorship |

Special Cases: Complex Scenarios

When Inventors Can’t Agree

The professor insists she conceived everything. The post-doc claims joint inventorship. Neither will sign the patent application.

Resolution Path:

- Document review by neutral patent counsel.

- Claim-by-claim analysis with both parties present.

- Focus on conception evidence, not feelings.

- If deadlock continues, file naming those who will sign, then petition to add others.

International Inventorship Differences

U.S. law requires naming all true inventors. Other countries may have different standards. A German employee might be an inventor under U.S. law but not German law—or vice versa.

Global Filing Strategy:

- Determine inventorship under U.S. standards first (typically strictest).

- Adjust for local requirements in each country.

- Document reasoning for any differences.

- Maintain consistent inventorship where possible.

AI-Assisted Invention

The machine learning model suggests a molecular structure. The researcher recognizes its potential and files a patent.

Who invented it? Current U.S. law requires human inventors. The researcher who recognized the value and reduced it to practice? Possibly. The programmer who created the AI? Generally no, unless the algorithm itself is claimed.

This area remains legally uncertain. Patent portfolio analysis helps identify AI-related inventorship risks in existing applications.

Post-Grant Inventorship Correction

The granted patent lists three inventors. Two years later, during licensing negotiations, the potential licensee’s diligence reveals a fourth person conceived element in claim 12.

Correction Without Court Intervention

Certificate of Correction under 35 U.S.C. § 256³:

- All current inventors must agree

- Omitted inventor must agree

- No deceptive intent in original error

- File request with $160 fee⁷

- Correction relates back to filing date

Timeline: 2-6 months typically

When Agreement Isn’t Possible

Federal Court Action:

- Omitted inventor can sue for correction

- Named inventors can petition for removal

- Court evaluates conception evidence

- If successful, court orders USPTO to correct

Timeline: 18-36 months typical litigation

Preserving Patent Validity During Correction

The key: demonstrating no deceptive intent. Courts examine:

- When was the error discovered?

- How quickly did you act?

- What documentation exists?

- Was information withheld from USPTO?

Good faith errors, promptly corrected, preserve patent validity³. Deliberate omissions, especially of known inventors, can be fatal.

Best Practices for Ongoing Inventorship Management

The patent portfolio contains 200 patents, 50 pending applications, and new filings monthly. Managing inventorship across this scale requires systems, not memory.

Documentation Standards

Laboratory Notebooks:

- Bound, numbered pages (no loose-leaf)

- Date every entry

- Describe conceptions specifically

- Regular witness signatures

- No gaps or post-dating

Electronic Records:

- Timestamped automatic systems

- Version control showing evolution

- Backup systems preventing loss

- Access logs showing who knew what when

Invention Disclosure Forms:

- Completed within 30 days of conception

- Signed by all potential inventors

- Reviewed by patent counsel

- Updated as understanding evolves

Team Education

Quarterly Training Topics:

- Conception vs. reduction to practice

- Importance of documentation

- Recognition of inventive moments

- Consequences of inventorship errors

Simple Message: If you think of something new that solves a technical problem, document it immediately and submit an invention disclosure—let patent counsel determine if you’re an inventor.

Regular Audits

Pre-Filing Review:

- Interview all technical contributors.

- Review all laboratory notebooks.

- Analyze all claims against contributions.

- Document inventorship rationale.

Post-Grant Monitoring:

- Annual inventorship confirmation.

- Update when claims change.

- Review when inventors leave.

- Verify before enforcement actions.

Special Situations Requiring Extra Care

High-Risk Scenarios:

- Academic collaborations with students

- Multi-company joint development

- Consultant contributions

- AI-assisted research

- International research teams

For these situations, implement enhanced documentation, more frequent reviews, and clear agreements before research begins.

Modern Challenges in Inventorship

Open Innovation Models

Companies increasingly crowd-source solutions. A pharmaceutical company posts a synthesis challenge. Hundreds submit proposals. The winning solution combines elements from multiple submissions.

Inventorship Complexity:

- Multiple potential inventors who never communicated

- Conception happening in parallel

- Difficulty proving who conceived first

- Platform terms of service vs. patent law

Risk Mitigation:

- Clear terms establishing inventorship rules

- Requirement for detailed documentation upon submission

- Rights assignment before revealing submissions

- Professional inventorship analysis before filing

Remote Collaboration

Team members across continents collaborate via video, shared documents, and asynchronous communication. Conception happens in Slack threads, Zoom calls, and collaborative whiteboards.

Documentation Challenges:

- Time zones affecting “date of conception”

- Ephemeral communication platforms

- Difficulty establishing who contributed what

- Cultural differences in claiming credit

Modern Solutions:

- Record key technical discussions

- Use persistent collaboration tools

- Regular inventorship checkpoint meetings

- Clear conception attribution practices

Rapid Development Cycles

Agile development. Daily iterations. Continuous deployment. The invention evolves constantly, making it difficult to pinpoint who conceived what.

Inventorship Tracking:

- Daily stand-ups include conception disclosures

- Sprint reviews document technical contributions

- Version control ties code to contributors

- Regular patent counsel involvement

The critical distinction: inventorship follows patent law, not academic authorship conventions. Papers list everyone who contributed. Patents name only those who conceived claimed elements. Organizations must communicate this difference clearly. Patent consulting helps develop customized policies for specific research environments.

Taking Action: The 5-Step Process

The patent certificate hangs on the wall. The names listed below “Inventors” will either protect or destroy the rights it represents. Follow this process to get them right:

Step 1: Map Every Technical Contributor – List everyone. The professor who had the idea. The student who ran experiments. The technician who suggested a parameter. The consultant who reviewed designs. Miss no one—omissions hurt more than inclusions.

Step 2: Analyze Conception, Not Contribution – For each person, identify what they mentally conceived versus what they physically did. The person who thought of the solution is the inventor. The person who built it is not—unless building it required conceiving new elements that appear in claims.

Step 3: Compare Against Every Claim – Take each contribution and search every claim. Does that exact technical element appear? Even in dependent claim 47? If yes, they’re an inventor. If no, they’re not—regardless of how hard they worked.

Step 4: Document Your Determination – Write down why each person is or isn’t listed. Reference specific conceived elements, claim limitations, and supporting evidence. This document saves you when memories fade and stories change.

Step 5: Review Regularly – Check inventorship before filing, after prosecution changes claims, and periodically post-grant. Claims evolve. New prior art surfaces. What seemed routine might prove inventive.

Your Immediate Action Plan

Today:

- List all pending applications—any inventorship concerns?

- Identify granted patents with known issues.

- Review employment agreements for assignment language.

This Week:

- Implement invention disclosure forms.

- Schedule team training on conception vs reduction.

- Establish documentation protocols.

This Month:

- Conduct portfolio-wide inventorship audit.

- Correct identified errors via USPTO procedures¹¹.

- Update collaboration agreements with inventorship terms.

The Stakes: Why This Matters

That line in the laboratory notebook—the one suggesting a different temperature—isn’t just a technical detail. It’s a potential patent killer.

Incorrect inventorship can:

- Invalidate patents completely with deceptive intent finding

- Make patents unenforceable even without bad intent³

- Eliminate standing to sue infringers

- Enable ownership claims by omitted inventors

- Trigger damages exceeding the patent’s value⁹

- Destroy reputations in tight-knit research communities

Patents have been invalidated over missing inventors. Universities have lost fundamental patents. These disasters were preventable with proper upfront determination.

Resource Toolkit

Documentation Templates:

- Invention Disclosure Form – Captures conception moment

- Contribution Matrix – Maps contributions to claims

- Inventorship Checklist – Step-by-step verification

- Collaboration Agreement Clauses – Legal language that works

- Laboratory Notebook Standards – Documentation that survives litigation

Official USPTO Resources:

- MPEP Chapter 1400 – Correction procedures

- Certificate of Correction – Fix procedures

- Inventorship Guidance – Official rules

Strategic Services:

- Patent Search Services – Prior art verification

- Ownership vs. Inventorship – Rights analysis

- Portfolio Analysis – Systematic review

- Patent Consulting – Complex scenarios

Frequently Asked Questions

Who qualifies as an inventor on a patent? Only those who conceive claimed elements. Not funders, not builders, not testers—unless they mentally formulated technical solutions that appear in claim language. Conception happens in the mind, not the lab. The key test for determining inventorship patent law requires mental formation of the complete solution.

What distinguishes inventorship from authorship? Patents require legal conception of claimed elements. Publications recognize all contributions. The technician who ran every experiment might be first author on the paper but not an inventor on the patent—unless they conceived claimed elements.

Can we correct inventorship after grant? Yes, through Certificate of Correction (if all agree), reissue application (if claims need change), or court order (if disputed). Without deceptive intent, correction preserves validity³. With deceptive intent, the patent may die. Proper inventorship correction USPTO procedures¹¹ protect patent validity.

What happens with incorrect inventorship? Best case: Correctable error requiring time and money. Worst case: Complete invalidation, loss of enforcement rights, ownership disputes, and damages. Severity depends on intent and materiality.

How do we handle collaborative research? Document everything contemporaneously. Apply claim-by-claim inventorship analysis. Focus on conception, not effort. Use formal agreements specifying determination procedures. Remember: contributing to one claim creates full joint inventorship determination.

Protect Your Patents with Expert Inventorship Analysis

The conception standard draws a bright line through the messy reality of innovation. One side: inventors with full rights. Other side: contributors with none. No middle ground exists.

This binary framework—harsh as it seems—provides clarity in a world of collaborative complexity. The graduate student who suggests one temperature becomes equal owner with the professor who conceived the core breakthrough. The technician who builds the prototype for months receives nothing unless they conceived claimed elements. Fair? Perhaps not. The law? Absolutely.

Master this framework now, before disputes arise. Document conception when it happens, not when lawyers ask. Analyze inventorship claim by claim, not contribution by contribution. Correct errors promptly while good faith still provides protection.

The patent hanging on your wall represents years of work, millions in investment, and your competitive future. The names listed below “Inventors” will determine whether it protects your innovation or becomes evidence in your opponent’s invalidity case.

Get those names right. Your entire portfolio depends on it.

Incorrect inventorship can destroy your entire patent portfolio.

Amir V. Adibi is an experienced patent attorney who provides:

- Comprehensive inventorship analysis before filing

- Documentation strategies that survive litigation

- Dispute resolution that preserves relationships

- Correction procedures that maintain validity

Don’t let a missing name invalidate your patents.

Schedule Your Inventorship Consultation

References

- Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Laboratories, Inc., 40 F.3d 1223 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

- Fina Oil & Chemical Co. v. Ewen, 123 F.3d 1466 (Fed. Cir. 1997).

- 35 U.S.C. § 256 – Correction of Named Inventor. Legal Information Institute.

- 35 U.S.C. § 116 – Inventors. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School.

- Eli Lilly & Co. v. Aradigm Corp., 376 F.3d 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

- Stern v. Trustees of Columbia University, 434 F.3d 1375 (Fed. Cir. 2006).

- Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Inc. v. Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., No. 19-2050 (Fed. Cir. July 14, 2020).

- American Intellectual Property Law Association. IPWatchdog, August 3, 2013.

- Patent Litigation Statistics. Legal Jobs, May 20, 2023.

- USPTO Fee Schedule. United States Patent and Trademark Office, 2024.

- MPEP § 1481.02 – Correction of Named Inventor. United States Patent and Trademark Office.

This guide provides educational information about U.S. patent inventorship law. It does not constitute legal advice for specific situations. Inventorship determination requires careful analysis of particular facts under current law. Consult qualified patent counsel for guidance on your inventorship questions.