An Information Disclosure Statement filed wrong—or filed late—can destroy an otherwise valid patent. Under 37 CFR 1.97, you have a continuing obligation to disclose material information to the USPTO, and how you meet that obligation determines whether your patent survives its first serious challenge. This guide covers the four timing windows for IDS submission, required fees and statements, and the verification steps that separate enforceable patents from expensive paperweights.

Key Takeaways

- File early for fee-free compliance. Submit your IDS within three months of filing or before the first Office Action—no fee, no statement required, guaranteed examiner consideration.

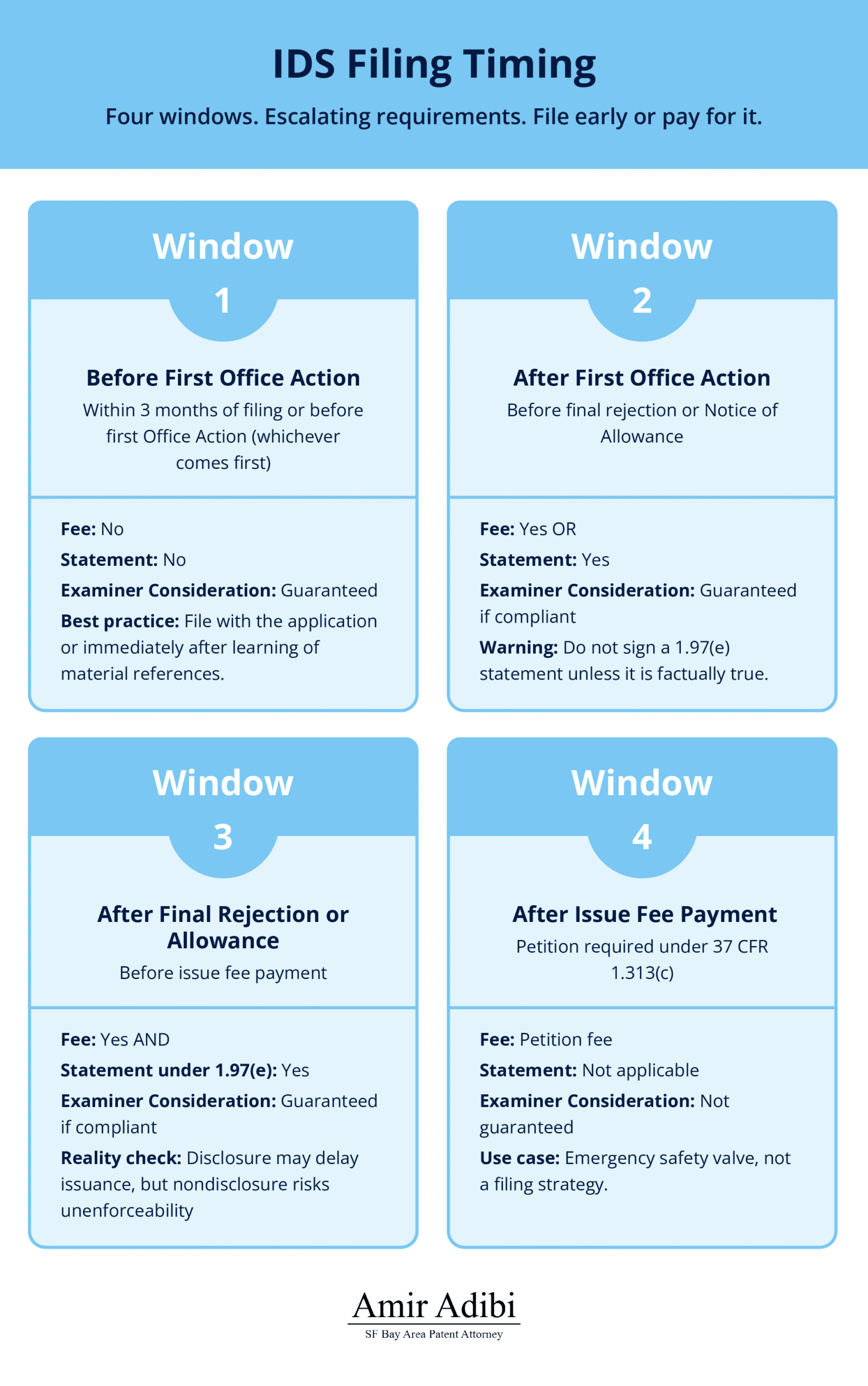

- Four windows, escalating requirements. Window 1 requires nothing extra; Window 2 requires fee OR statement; Window 3 requires BOTH; Window 4 requires a petition with no guarantee of consideration.

- Materiality means what an examiner would want. Disclose anything a reasonable examiner would consider important in deciding patentability—when uncertain, disclose.

- Inequitable conduct kills patents. Since Therasense v. Becton Dickinson (2011), the “but-for” materiality standard is demanding, but a finding of inequitable conduct still renders the entire patent unenforceable.

- Filing isn’t enough—verify consideration. Check that your references appear on the issued patent with examiner initials; references without initials weren’t formally considered.

- Patent Center is your filing portal. EFS-Web was retired in November 2023; use Patent Center for all electronic IDS submissions.

IDS Filing Requirements: The Four Timing Windows

Four windows. Escalating requirements. One principle: file early.

Under 37 CFR 1.97, each timing window adds requirements. Submit in the first window and you owe nothing beyond the IDS itself. Wait too long, and you’re paying fees, signing statements, or petitioning the USPTO to reconsider an application already cleared for issuance.

The safest path is also the simplest: file within three months of your application filing date or before the first Office Action, whichever comes first. No fee. No statement. Guaranteed examiner consideration. Everything after that costs more and protects less.

Window 1: Before First Office Action (No Fee, No Statement)

This is the window you want. Submit your IDS before receiving the first Office Action on the merits, or within three months of your filing date (whichever comes first), and you owe nothing beyond the submission. The examiner must consider your references.

The trap: these two thresholds compete. If you file on January 1 and receive a first Office Action on February 15, your fee-free window closed February 15, not April 1. If three months pass without any Office Action, the window still closes at the three-month mark.

Don’t gamble on timing. If you have material references when you file your application, submit the IDS simultaneously. If references surface during early prosecution, file immediately rather than hoping to beat the first Office Action.

Window 2: After First Office Action, Before Final Rejection or Allowance

The first Office Action has arrived. The requirements escalate—modestly.

You must now include either:

- The IDS fee (the fee specified in 37 CFR 1.17(p); verify current amounts at uspto.gov), OR

- A statement under 37 CFR 1.97(e)

One or the other. Not both.

The 1.97(e) statement certifies one of two facts:

- Foreign counterpart prong: The reference was first cited in a communication from a foreign patent office in a counterpart application, received within the last three months, OR

- Newly learned prong: The reference first became known to any person with a disclosure duty within the last three months.

If either statement is true, you avoid the fee. If neither is true—you’ve known about the reference for more than three months and no foreign examiner recently cited it—pay the fee.

The mistake that matters: signing a 1.97(e) statement when the facts don’t support it. That certification enters the prosecution history permanently. If later shown false, you’ve created evidence of intent to deceive—half the equation for inequitable conduct.

Window 3: After Final Rejection or Notice of Allowance

Final rejection or Notice of Allowance in hand? The requirements tighten again. Now you need both the fee and a 1.97(e) statement. Neither alone suffices.

This window demands attention when you receive a Notice of Allowance and then discover material prior art. Between receiving allowance and paying the issue fee, you can still file an IDS with fee and statement, and the examiner must consider it.

The strategic reality is uncomfortable but clear: filing at this stage delays issuance, costs money, and may reopen prosecution. Yet failing to disclose creates far greater risk. A late IDS fee is trivial next to a patent declared unenforceable in litigation.

Window 4: After Issue Fee Payment (Petition Required)

Once you’ve paid the issue fee, the rules change fundamentally. You cannot file an IDS as a matter of right. Instead, you must petition under 37 CFR 1.313(c) to withdraw the application from issuance.

Key realities at this stage:

- The petition may be denied. Unlike earlier windows, compliance doesn’t guarantee consideration.

- Issuance is delayed. You’re asking the USPTO to pull your application back from the finish line.

- Costs multiply. Petition fees, potential additional prosecution, delay—all compound.

This window is a safety valve, not a strategy. Arriving here means something failed earlier in your disclosure process.

Quick Reference: IDS Timing Requirements

| Timing Window | Fee Required? | Statement Required? | Examiner Consideration |

| Before 1st Office Action / within 3 months | No | No | Guaranteed |

| After 1st Office Action, before final/allowance | Yes OR | Yes OR | Guaranteed if compliant |

| After final rejection or Notice of Allowance | Yes AND | Yes AND | Guaranteed if compliant |

| After issue fee payment | Petition fee | N/A | Not guaranteed |

Fee amounts change. Verify current USPTO fees at uspto.gov before filing.

Understanding Your Duty of Disclosure Under Patent Law

Now that you understand when to file, the question becomes what you’re required to disclose, and why the answer matters more than any fee.

What 37 CFR 1.97 Actually Requires

The IDS rules serve a deeper obligation: the duty of candor and good faith under 37 CFR 1.56.

Everyone substantively involved in prosecution carries this duty:

- Each named inventor

- The prosecuting attorney or agent

- Anyone substantively involved in preparing or prosecuting the application

This obligation runs continuously from filing through issuance. Material information surfacing at any point during prosecution triggers disclosure requirements.

The companion regulation, 37 CFR 1.98, specifies content requirements—forms, copies, reference identification. Together, 1.97 (timing) and 1.98 (content) form the complete procedural framework for patent prosecution IDS compliance.

Defining “Material” Information: The Reasonable Examiner Standard

The duty covers all information “material to patentability.” Defining what qualifies as material is where judgment enters.

Under 37 CFR 1.56(b), information is material if it’s not cumulative to existing record and either:

- Establishes a prima facie case of unpatentability, or

- Refutes or contradicts a position taken by the applicant on patentability

The practical test: would a reasonable patent examiner consider this information important in deciding whether to allow the claims?

Commonly material information includes:

- Prior art patents or publications disclosing claimed elements

- Office Actions from related applications addressing similar claims

- Foreign search reports examining counterpart applications

- Litigation statements bearing on claim scope or validity

- Prior public uses, sales, or disclosures of the invention

Gray areas require judgment. A tangentially related reference may not be material. A reference highly relevant to dependent claims but not independent claims still needs disclosure.

The governing principle: when in doubt, disclose. Submitting one additional reference costs minutes of attorney time. Having that reference surface in litigation—with opposing counsel arguing intentional concealment—can cost the patent.

The Connection to Prior Art Under 35 U.S.C. 102

Your IDS puts prior art before the examiner for evaluation against novelty and non-obviousness requirements.

Disclosure doesn’t admit invalidity. It ensures the examiner can consider the reference. The examiner then determines whether it qualifies as prior art under 35 U.S.C. 102 and whether claims remain patentable in view of it.

This evaluation happens regardless of your own assessment. Even if you believe a reference is distinguishable, disclosure lets the examiner independently evaluate relevance—strengthening the resulting patent’s presumption of validity.

How to File an IDS: Forms, Content, and Procedure

Filing requires precision. Procedural errors don’t just delay examination—they can result in references being overlooked entirely.

Required USPTO Forms

The USPTO provides standardized forms for IDS submission:

- PTO/SB/08A — U.S. patent documents

- PTO/SB/08B — Foreign patent documents and non-patent literature (NPL)

These forms are available at uspto.gov. Each listed reference requires specific identifying information: patent numbers, publication dates, inventor names, and titles.

Content Requirements Under 37 CFR 1.98

Beyond the forms themselves, 37 CFR 1.98 mandates:

For U.S. patents and published applications: Document number and issue/publication date. No copies required—the USPTO has access.

For foreign patents: A copy of the document. If not in English, a translation or statement of relevance may be required for examiner consideration.

For non-patent literature: A complete copy. This includes journal articles, technical papers, product manuals, or any other written material. Partial copies or citations without copies don’t satisfy the requirement.

For references in non-English languages: Either a complete English translation or a concise statement explaining relevance. Without one or the other, the examiner may not consider the reference.

Electronic Filing Through Patent Center

Practitioners file through USPTO’s electronic filing system, Patent Center. (Note: The legacy EFS-Web system was retired in November 2023.)

Electronic submission generates immediate confirmation receipts. These receipts prove filing date, which can be critical when timing windows are close. Save confirmation documentation immediately and store it with the application file.

Common electronic filing pitfalls:

- Large documents may fail upload—check file size limits.

- System maintenance windows can block filing at critical deadlines.

- Confirmation pages must be saved; they’re not always retrievable later.

Confirming Examiner Consideration of IDS References

Filing an IDS doesn’t automatically mean the examiner reviewed each reference. You must verify.

On issued patents, references considered by the examiner appear with examiner initials on the front page and in the prosecution record. References listed without initials weren’t considered—meaning they don’t carry the weight of examiner review.

To verify:

- Check the issued patent’s front page for cited references with examiner initials.

- Review Patent Center for the IDS listing in the file wrapper.

- Confirm each submitted reference appears with notation of examiner consideration.

If references lack examiner acknowledgment, investigate. The issue may be procedural (filed in the wrong format, missing copies) or substantive (examiner overlooked the submission). Depending on timing, supplemental submission or petition may be appropriate.

Consequences of Non-Compliance: Inequitable Conduct and Unenforceability

The stakes extend far beyond examination. Failure to comply with disclosure obligations can render the entire patent unenforceable.

The Inequitable Conduct Defense in Patent Litigation

When patents reach litigation, defendants search for weaknesses. Inequitable conduct is among the most potent defenses available.

The standard requires proving two elements:

- Materiality: The withheld information was material to patentability

- Intent: The applicant intended to deceive the USPTO

Since Therasense, Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson & Co., courts apply a demanding standard: the withheld reference must be “but-for” material (meaning the patent wouldn’t have issued with proper disclosure) and intent must be the single most reasonable inference from the evidence.

Despite this heightened standard, the defense remains viable—and devastating when successful. A finding of inequitable conduct renders the entire patent unenforceable, not just claims related to the withheld reference.

Real-World Implications

Patent portfolios function as business assets. An unenforceability finding affects:

- Licensing revenue and existing agreements

- Acquisition valuations where patents support transaction price

- Enforcement capability against infringers

- Collateral value in secured financing

The risk is asymmetric: proving inequitable conduct is difficult, but raising the allegation justifies extensive discovery into prosecution decisions. Even unsuccessful claims create expense and uncertainty.

In licensing negotiations, sophisticated parties conduct similar diligence. A patent with potential disclosure gaps carries diminished value, regardless of whether inequitable conduct could ever be proven.

Prevention: Building a Strong Disclosure Practice

Defense is straightforward in concept and requires discipline in execution:

- Disclose early: First timing window, whenever possible.

- Disclose broadly: Uncertain about materiality? Disclose. Over-disclosure costs minutes; under-disclosure can cost everything.

- Document decisions: If you conclude a reference isn’t material and don’t disclose, document that analysis contemporaneously. A reasoned record beats a suspicious gap.

- Coordinate across applications: References cited in one application deserve consideration for disclosure in related applications.

- Monitor continuously: The duty runs throughout prosecution. Foreign examiner citations, litigation discoveries, ongoing searches—all trigger potential obligations.

If you’re uncertain whether your practices meet the standard, a patent attorney can audit your process and identify gaps before they become vulnerabilities.

Special Situations and Advanced Considerations

Managing IDS for Foreign Counterpart Applications

Foreign prosecution creates U.S. disclosure obligations. When a foreign examiner cites prior art in a counterpart application, you typically have three months to file a U.S. IDS using the 1.97(e) statement (if you’re in the second timing window). Beyond three months, you can still file but must pay the fee.

Coordination strategies for international portfolios:

- Establish monitoring: Ensure prompt notice when foreign examiners cite references.

- Track citation dates: The three-month clock runs from receipt of the foreign communication, not issuance.

- Centralize tracking: For large portfolios, maintain a master tracker linking each application to its foreign family and prosecution status.

Complexity scales with portfolio size. A single invention prosecuted in five countries generates multiple examination reports with different cited references—each potentially triggering disclosure obligations everywhere else.

IDS Timing in RCEs and Continuation Applications

Requests for Continued Examination and continuation applications create timing questions.

RCEs: Filing an RCE reopens prosecution. Timing windows reset with respect to post-RCE Office Actions. But your knowledge date doesn’t reset—references you knew before the RCE don’t get a fresh three-month window.

Continuations: A continuation is a new application with its own timing windows based on its own filing date and Office Actions. The duty to disclose references known from the parent continues. References cited in the parent merit consideration for the continuation.

The principle: new applications and RCEs may provide fresh procedural windows, but the substantive duty to disclose what you already know remains continuous.

Inventorship and Disclosure Obligations

Every named inventor carries disclosure duties under 37 CFR 1.56. The prosecuting attorney must gather this information.

For multi-inventor applications:

- Each inventor should be asked about relevant prior art.

- Inventors who depart or become unavailable still have duties (document reasonable efforts to obtain information).

- Technical team members beyond named inventors may have knowledge—consider anyone “substantively involved in preparation or prosecution”.

For guidance on identifying who should be named as an inventor—and therefore subject to disclosure duties—see Determining Proper Patent Inventorship.

IDS Best Practices Checklist

- File early — Within 3 months or before first Office Action

- Use correct forms — PTO/SB/08A for U.S. references; PTO/SB/08B for foreign and NPL

- Include required copies — All foreign patents and all NPL

- Match requirements to timing — Pay fees and include statements as your window requires

- Save confirmation receipts — Immediately after electronic submission

- Verify examiner consideration — Check issued patent and file wrapper for initials

- Monitor foreign counterparts — Track citations from international prosecution

- Document disclosure decisions — Contemporaneous records of materiality analysis

- When in doubt, disclose — Minimal cost, maximum protection

IDS Compliance as Enforceability Insurance

The rules under 37 CFR 1.97 exist for a reason beyond procedural tidiness. They form the framework for a legal duty that determines whether your patent survives adversarial scrutiny.

Think of compliant IDS filing as enforceability insurance. The premium is low—attorney attention and timing discipline. The coverage is substantial—a prosecution record demonstrating good-faith disclosure that withstands challenge.

Three principles matter most:

- File early. The first window costs nothing and guarantees consideration.

- Document everything. Your future litigation counsel will thank you for contemporaneous records of what you knew, when you knew it, and why you made the decisions you made.

- Verify review. Filing isn’t enough. Confirm references appear on the issued patent with documented examiner consideration.

When stakes are high and rules are nuanced, professional guidance earns its cost.

Need help navigating IDS requirements or building a compliant disclosure process? Contact Amir Adibi for expert guidance on patent prosecution strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an Information Disclosure Statement (IDS)?

An IDS is a formal USPTO submission listing prior art and other material information relevant to your application’s patentability. Filing an IDS fulfills your duty of disclosure under 37 CFR 1.56.

When must an IDS be filed under 37 CFR 1.97?

An IDS can be filed throughout prosecution, but requirements vary by timing. The easiest window—before first Office Action or within three months of filing—requires no fee and no statement.

What fees are required for IDS filing?

No fee if filed before the first Office Action. After that, fees apply based on timing. Verify current amounts at the USPTO fee schedule, as fees change.

What is the 37 CFR 1.97(e) statement?

A certification that either (1) the information was cited in a foreign counterpart within the last three months, or (2) the information became known to someone with disclosure duty within the last three months.

What happens if I fail to file an IDS properly?

Failure to disclose material information can result in inequitable conduct findings, rendering the entire patent unenforceable—not just claims related to the undisclosed reference.

This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Consult a qualified patent attorney for guidance on your specific situation.