The test is simple: Your invention qualifies as “truly new” under 35 U.S.C. 102 if no single prior art reference discloses all elements of your claimed invention before your effective filing date. One missing element, and you pass the novelty bar.

Three dates that control your patent fate:

- Your first public disclosure (starts the 12-month U.S. grace period clock)

- Your effective filing date (the USPTO’s measuring stick for prior art)

- Any competitor’s filing date (under first-inventor-to-file, the earliest filer wins)

The mistakes that kill patents: Public disclosure before filing. Underestimating what counts as “public”—beta launches, investor demos, crowdfunding campaigns. Failing to document your invention timeline until it’s too late.

What to do now: If you’ve disclosed publicly, you likely have less than 12 months to file in the U.S.—and may have already lost foreign rights. If you haven’t disclosed, file first. Either way, a prior art search now costs less than a rejected application later.

A scenario for example: The term sheet sits on the conference table. Series A. Her lead investor has one condition: a patent filing before close. Eighteen months of building proprietary recommendation algorithms, and she’s finally ready to protect them.

Forty-five minutes later, she learns that the conference presentation she gave eight months ago—the one that landed her first enterprise customer—started a clock she didn’t know existed. Worse, a quick search reveals a competitor filed a similar application two months before her presentation.

Her $35,000 patent budget might be worthless.

This happens constantly. It’s almost always preventable.

Here’s what she needed to know: Under 35 U.S.C. 102, your invention is novel if no single piece of prior art discloses every element of what you’re claiming. The patent novelty requirements are precise—the question isn’t whether someone had a similar idea. It’s whether someone already put your exact combination of elements into the public domain—or filed it—before you did.

The stakes are substantial. A utility patent application runs $10,000 to $35,000 in attorney fees depending on complexity, plus USPTO fees, plus maintenance fees over twenty years. When 35 USC 102 prior art surfaces during examination—or worse, during litigation after you’ve built a business around that patent—the loss extends far beyond filing costs.

This guide gives you the framework to avoid that outcome. You’ll learn what qualifies as prior art under the America Invents Act, how to calculate your critical dates, and how to structure a filing strategy that maximizes protection. No legalese without explanation. No theory without application.

Key Takeaways

- The novelty standard: Under 35 U.S.C. 102, your invention is “truly new” only if no single prior art reference discloses every element of your claimed invention before your effective filing date.

- First-inventor-to-file controls: Since March 16, 2013, the U.S. has operated under a first-inventor-to-file system—whoever files first generally wins, regardless of who invented first.¹

- Five categories of prior art can block your patent: patents, printed publications, public use, on-sale activity (including confidential sales per Helsinn v. Teva), and anything otherwise available to the public.²

- The 12-month grace period is narrower than it appears: Your own disclosure doesn’t count against you if you file within 12 months, but it doesn’t protect against earlier filers—and most foreign countries don’t recognize it.

- International implications vary: Europe (EPO) and China have very limited or no meaningful grace periods. Japan and South Korea offer 12-month grace periods but with stricter procedural requirements than the U.S.

- Prior art searches are essential: A professional search costing $1,000 to $3,000 can reveal blocking references before you invest $20,000+ in prosecution.

- Documentation is critical: Preserve dated engineering notebooks, email threads, NDA records, and publication timestamps—you may need to prove facts about dates years later.

Understanding 35 USC 102 Prior Art Under the America Invents Act

The America Invents Act took effect on March 16, 2013, and fundamentally rewrote how the United States decides who gets a patent.¹ These aren’t academic distinctions. They determine whether you own your innovation or watch a competitor claim it.

The Transition to First-Inventor-to-File: What It Means for Your Patent Strategy

Before the AIA, the U.S. operated on “first-to-invent.” If you could prove you invented before a competitor—even if they filed first—you could win the patent through an interference proceeding. Lab notebooks mattered. Dated prototypes mattered. Documentation of conception mattered.

That world is gone.

Under first-inventor-to-file, whoever files first gets the patent. Your filing date is now your most valuable asset. The date you conceived the idea, the nights in the garage, the napkin sketch—none of it matters if someone else files before you.

The shift in practice:

| Pre-AIA (Before March 16, 2013) | Post-AIA (Current System) |

| First to invent could win | First to file wins |

| Interference proceedings resolved disputes | No interference; filing date controls |

| Invention date documentation critical | Filing date documentation critical |

| U.S. was globally unique | U.S. now harmonized with most of world |

That last row matters for international strategy. Europe, Japan, China, Korea—all first-to-file, always have been. The AIA brought the U.S. into alignment, simplifying international filing but eliminating the “prove your invention date” safety net that once existed domestically.

Your action: Stop proving when you invented. Start filing faster. If you’re not ready for a full non-provisional application, file a provisional to stake your priority date.

Breaking Down 35 USC 102(a): Five Categories of Prior Art That Can Destroy Your Patent

Section 102(a) defines the universe of existing knowledge your invention must be novel against. Two subsections, different mechanics.

102(a)(1) — Public Prior Art

Anything publicly available before your effective filing date:

- Patented: Any patent, anywhere in the world, published before your filing date. A Japanese patent from 1987? Prior art. An expired U.S. patent from 1952? Still prior art.

- Described in a printed publication: Journal articles, conference papers, technical manuals, white papers, blog posts, archived web pages. The standard: could someone skilled in the field locate it with reasonable diligence?

- In public use: Someone using your invention publicly in the U.S. before your filing date. “Public” doesn’t require commercial sale—a trade show demonstration qualifies.

- On sale: The invention offered for sale, even once, even if no sale completed. After the Supreme Court’s 2019 Helsinn Healthcare v. Teva decision, even confidential sales can trigger this on-sale bar—the Court held unanimously that a sale to a third party under a confidentiality agreement may place the invention “on sale” under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(1).²

- Otherwise available to the public: The catch-all: oral conference presentations, poster sessions, YouTube videos, product demos. If the public could access it, it counts.

102(a)(2) — Secret Prior Art

This is the trap founders don’t see coming.

If someone else filed a patent application before your filing date, that application is prior art against you even if it wasn’t published when you filed.

Picture this: You file on June 1. A competitor filed on April 1, but under the 18-month publication delay, their application won’t be visible until October of the following year.³ You couldn’t have known it existed. It still blocks you.

Speed matters even when you believe you’re first. You’re not racing public information. You’re racing filings you cannot see.

What this looks like in practice:

- SaaS: A competitor’s API documentation on GitHub from six months ago describes your authentication method. Prior art.

- Hardware: A Kickstarter campaign showed a prototype with your mechanical innovation. Prior art—even if they never shipped.

- Biotech: A conference poster described your compound’s mechanism of action. Prior art, even without formal publication.

Grace Period Exceptions Under 102(b): Your One-Year Safety Net

Section 102(b) provides a limited exception—a 12-month grace period for inventor disclosures. But this exception is narrower than most founders assume and more dangerous than it appears.

How it works:

If you (the inventor, or someone who obtained the information from you) publicly disclosed your invention, that disclosure doesn’t count as prior art against you if you file within 12 months.

Additionally, if someone else independently discloses the same invention after your disclosure, their disclosure doesn’t count against you either. Your public disclosure essentially inoculates you against subsequent disclosures of the same subject matter.

The limitations that matter:

The clock starts immediately. Present at a conference on March 15, and you must file by March 15 of the following year. Miss it by a day, and you’ve lost U.S. patent rights.

It doesn’t protect against earlier filers. If a competitor files before your disclosure date, you lose—grace period or not. The exception only prevents your own disclosure from becoming prior art.

International implications vary significantly. Europe (EPO) and China have very limited or no meaningful grace periods—in Europe, the grace period applies only to abusive disclosures or officially recognized international exhibitions. Japan and South Korea have 12-month grace periods, but with stricter procedural requirements than the U.S.—requiring formal declarations with evidence submitted within 30 days of filing. Disclose publicly before filing, and you may preserve U.S. rights while permanently losing the ability to patent in markets that matter to your business. Critical Warning: If international patent rights matter to your business, treat the grace period as a last resort, not a strategy. File before you disclose.

Documentation if you rely on it:

You’ll need to prove the chain. Who disclosed? When exactly? What was disclosed? Dated presentation slides, conference programs, timestamped emails—these establish that the prior art originated from you and that you filed within 12 months.

Calculating Critical Dates: A Founder’s Timeline Checklist

Your “effective filing date” anchors all prior art analysis. Everything public or filed before this date is potential prior art. Everything after is not.

Step 1: Identify your earliest filing

Your effective filing date is typically when you filed your application. But it can be earlier if you filed a provisional application first (and the non-provisional claims are supported by it), claimed priority to a foreign application under the Paris Convention, or filed through the PCT system.

Step 2: Verify your priority chain

Claiming an earlier date from a provisional or foreign application requires that application to adequately support your current claims. “Adequately support” means written description under 35 U.S.C. 112—the earlier application must describe what you’re now claiming in enough detail that a skilled practitioner would recognize you possessed the invention.

Thin provisionals fail here constantly. A two-page provisional filed hastily before demo day may not support the detailed claims you want a year later. If the USPTO determines your provisional doesn’t support your claims, your effective filing date reverts to your non-provisional date, and everything between becomes potential prior art.

Step 3: Map your disclosure timeline

Every potential public disclosure needs a date: conference presentations (including submission dates, not just presentation dates), published papers (preprint servers count—arXiv, medRxiv), product launches and beta releases, crowdfunding campaigns, investor decks shared without NDAs, press coverage and interviews, social media posts showing the invention, trade show appearances, academic thesis submissions.

For each disclosure, determine: Did it happen before or after your effective filing date? If before, does the grace period apply?

Step 4: Assess competitor activity

Search for competitor applications filed before your effective filing date. Remember—they may not be published yet. You won’t know about them until 18 months after their filing date.³ You might file, wait, and then discover blocking prior art you couldn’t have found.

This uncertainty rewards speed.

Strategic Application of Patent Novelty Requirements for Inventors and Startups

Understanding the law is necessary but not sufficient. You need strategies that translate legal knowledge into business protection.

Conducting Prior Art Searches That Actually Protect You

A prior art search serves two purposes: identifying barriers to your patent and discovering opportunities for stronger claims. Many founders skip this step or run superficial searches. Both are mistakes.

Free resources to start:

Google Patents offers broad coverage with full-text search across international patents—a reasonable starting point, but with limited precision. The USPTO Patent Full-Text Database covers U.S. patents and published applications with Boolean search capability. Espacenet from the European Patent Office provides worldwide coverage. WIPO PATENTSCOPE covers PCT applications and international search reports.

The danger zone: non-patent literature

The prior art most likely to kill your patent often isn’t in a patent database. Non-patent literature includes academic journals (IEEE, ACM, PubMed), conference proceedings, technical standards documents, industry white papers, product manuals, archived websites via the Wayback Machine, doctoral dissertations, and foreign technical publications.

For biotech founders, this means PubMed, clinical trial registries, and scientific conference archives. For SaaS founders: GitHub repositories, technical blog posts, archived API documentation.

When to go professional:

DIY searches work for initial orientation. But before investing $20,000+ in a patent application, a professional patent search from specialists who understand classification codes, precise query construction, and relevance assessment is worthwhile. Professional searches typically range from $1,000 to $3,000 depending on complexity and depth of analysis. A comprehensive search that reveals a blocking reference saves far more in wasted prosecution.

The Anticipation Test: Determining if Prior Art Really Blocks Your Patent

Finding prior art doesn’t end the analysis. The question is whether that art anticipates your claims—and anticipation has specific requirements.

The all-elements rule:

A reference anticipates only if it discloses every single element of your claim, arranged as your claim arranges them. Claim A + B + C, and the prior art shows A + B but not C? No anticipation. Prior art shows A + B + C + D? That does anticipate—extra elements don’t save you.

This is why claim drafting matters enormously. A skilled attorney can often draft around prior art by adding or specifying elements the art lacks.

Inherency:

Sometimes prior art doesn’t explicitly state an element, but that element is necessarily present. A process that inherently produces your claimed result—even if the reference never mentions it—can still anticipate. This arises frequently in chemical and biotech patents.

Responding to 102 rejections:

When the USPTO issues a 102 rejection based on prior art, you have paths forward: amend claims to add distinguishing limitations, argue that the prior art doesn’t actually disclose all elements, challenge whether the reference qualifies as prior art (wrong date, not actually public), or in limited circumstances, establish an earlier invention date (rare under AIA).

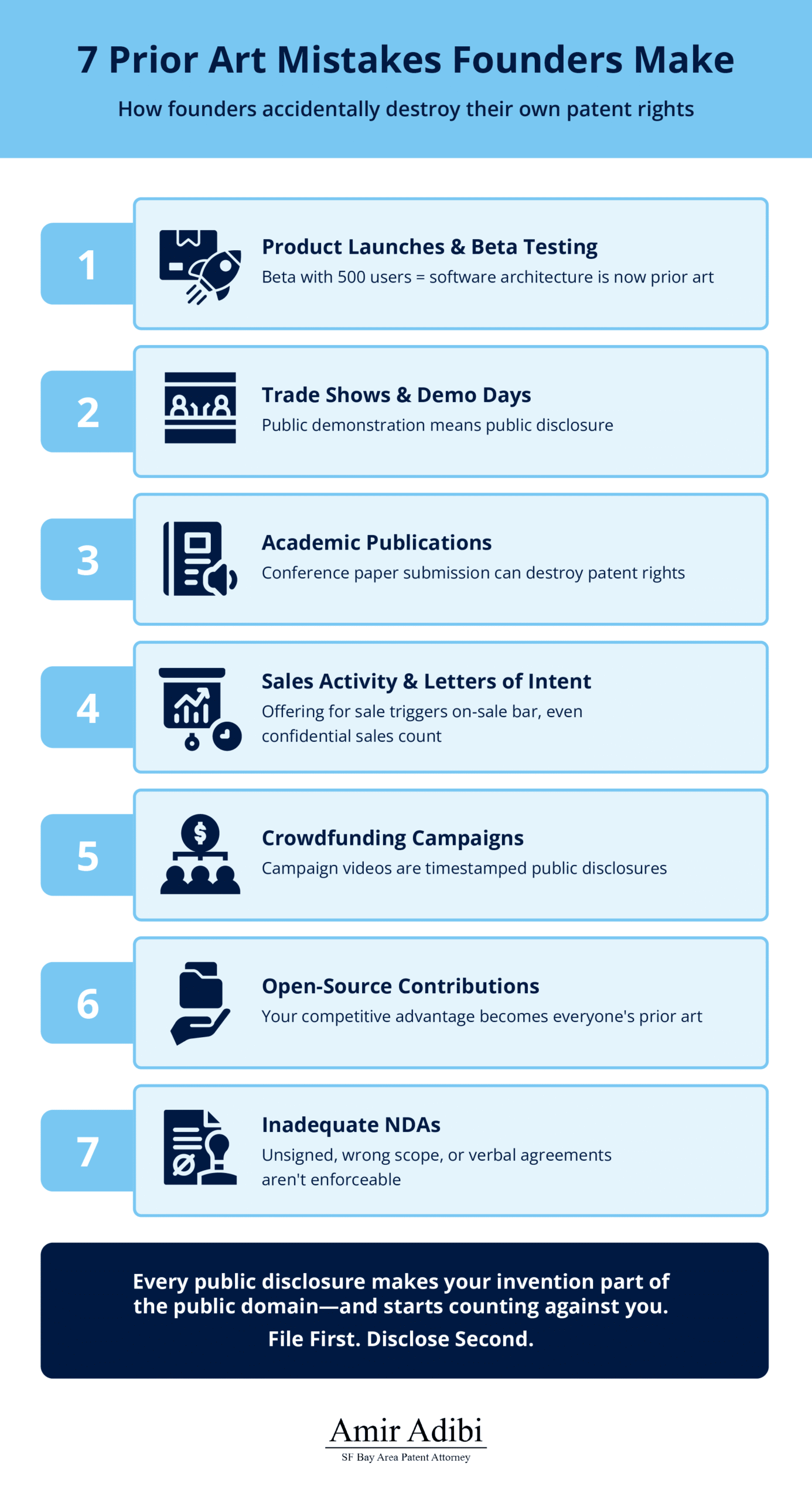

Seven Common Prior Art Mistakes Founders Make (And How to Avoid Them)

Founders create their own prior art problems with alarming regularity. Here are the patterns that surface most often.

1. Premature product launches and beta testing

“Soft launch” and “beta” carry no legal magic. Real users accessing your product means it’s public. A beta with 500 users means your software architecture is now prior art.

The fix: File a provisional before external access, or use genuinely private testing with signed NDAs and controlled access.

2. Trade shows and demo days

Demonstrating your hardware prototype at CES, your AI model at Y Combinator demo day—the public saw it. It’s public.

The fix: File a provisional before the event. If you’re demoing, assume disclosure.

3. Academic publications and conference presentations

If you have co-founders from academia, this is your highest-risk category. Researchers publish—that’s how careers advance. A conference paper submitted three months before you considered filing a patent can destroy your rights.

The fix: Patent review happens before paper submission, not after. Build this into your academic collaboration agreements.

4. Sales activity and letters of intent

Offering your product for sale—even without completing a sale—triggers the on-sale bar. After Helsinn, even a confidential sale to one customer under NDA can count.² If the product was ready for patenting and you made a commercial offer, you’ve created prior art.

The fix: File before sales activity. If you must discuss terms with early customers, avoid specific commercial offers. File immediately after.

5. Crowdfunding campaigns

Kickstarter, Indiegogo—these are public disclosures. Your campaign video showing how the invention works is prior art. Timestamped.

The fix: File a provisional before launch. Non-negotiable for crowdfunded hardware.

6. Open-source contributions

Contributing code that embodies your invention to an open-source project makes that code public. Your startup’s competitive advantage becomes everyone’s prior art.

The fix: Maintain proprietary separation between patentable innovations and open-source contributions. File before you contribute.

7. Inadequate NDAs

NDAs fail not because they don’t exist, but because they’re unsigned, they don’t cover the right subject matter, or they’re unenforceable. A verbal understanding that a meeting is “confidential” isn’t an NDA.

The fix: Written NDAs, signed before disclosure, specifically covering patent-related information. Even strong NDAs don’t help once you’ve disclosed to enough people that information inevitably leaks.

Filing Strategies Under First-Inventor-to-File: A Decision Framework

Your filing strategy balances speed, cost, and coverage.

Provisional applications: your placeholder

A provisional establishes a priority date without the cost of a full application. It’s never examined and expires after 12 months without a non-provisional follow-up—the 12-month pendency period cannot be extended.⁴

When to use one: You need to disclose soon but aren’t ready for full claims. You’re testing market fit and may pivot. Budget requires phased investment. You need a priority date before a funding round or trade show.

The warning: Thin provisionals provide false security. If your non-provisional claims aren’t supported by the provisional’s disclosure, you don’t get the earlier date. Invest in a provisional that comprehensively describes your invention.

Non-provisional applications: your real filing

Examined by the USPTO, can become a patent. File directly or convert from a provisional.

When to file directly: Your invention is mature with clear claims. You need examination started for licensing or litigation. You’re confident you won’t need provisional flexibility.

Continuation strategies:

Continuations let you pursue additional claims based on an earlier filing’s priority date—valuable when technology evolves, when initial claims are rejected but other angles exist, or when competitors design around your issued patent.

For a comprehensive approach to continuation and filing strategy, a patent portfolio analysis can align your IP investments with business objectives.

Defensive publication:

If you want to prevent competitors from patenting an idea but don’t want to invest in your own patent, defensive publication makes the invention public—turning it into prior art against anyone who files later, including you.

When it makes sense: The invention has blocking value but not enforcement value. Budget constraints make prosecution impractical. You’re in a fast-moving field where published prior art is more defensible than pending applications.

Post-Grant Defense: Protecting Your Patent from 102 Challenges

Getting a patent issued is half the battle. Defending it against invalidity challenges is the other half.

Common 102 invalidity arguments:

In litigation and inter partes review (IPR), challengers search for prior art the USPTO examiner missed: references you didn’t cite, publications or products you weren’t aware of, your own disclosures that fall outside the grace period, earlier-filed applications that published after your filing.

IPR and PGR vulnerability:

Inter partes review lets anyone challenge your patent at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board based on patents and printed publications—limited to novelty and obviousness grounds under §§ 102 or 103.⁵ Post-grant review, available within nine months of grant, allows challenges on any ground—including on-sale bar and public use.⁶

Minimize exposure by conducting thorough searches before filing, documenting your disclosure timeline, preserving evidence of what you disclosed and when, and ensuring your disclosure comprehensively supports your claims.

Evidence preservation:

If your patent faces a 102 challenge years after issuance, you’ll need to prove facts about dates and disclosures. Preserve dated engineering notebooks and prototypes, email threads establishing timelines, NDA records with signatories, documentation of pre-filing disclosures, and publication records with precise dates.

Your 35 USC 102 Action Plan

For founders building patent-dependent businesses, understanding 35 U.S.C. 102 prior art rules isn’t optional. It’s the foundation of IP strategy.

30-60-90 Day Timeline:

Days 1-30: Conduct initial prior art search using free tools. Map your complete disclosure timeline. Identify any disclosures that started a grace period clock. Assess whether foreign filing matters to your business.

Days 31-60: Commission a professional prior art search if initial results are promising. Draft or refine your provisional if you haven’t filed. Implement disclosure controls—NDAs, publication review processes. Document invention dates and inventor contributions.

Days 61-90: File provisional or non-provisional based on search results. Establish strategy for continuations and international coverage. Create calendar alerts for critical dates: grace period expiration, provisional 12-month deadline.

Red flags requiring immediate attorney consultation:

You’ve publicly disclosed and haven’t filed within 12 months. You’re preparing for international filing after U.S. disclosure. A competitor has filed or issued a patent in your space. You’ve received a 102 rejection and aren’t sure how to respond. You’re facing IPR or litigation with invalidity claims. You have academic co-founders publishing in your technology area.

Cost-benefit reality check:

Not every invention needs a patent. Before investing $20,000 to $50,000+ in prosecution, ask: Does your competitive advantage depend on exclusivity? Will competitors copy without protection? Does your market value patents for licensing, acquisition, or investment? Can you enforce if infringed? Is the invention fundamental or easily designed around?

If the answers favor patenting, 35 U.S.C. 102 analysis is your first step. If they don’t, invest those resources elsewhere.

Your next step:

If prior art questions are shaping your patent strategy—or if you’re unsure whether they should be—get clarity now. Schedule a prior art consultation to assess your novelty position before you invest in filing.

Common Questions About 35 USC 102

What is the difference between 35 USC 102 and 103?

Section 102 addresses novelty—whether your exact invention exists in the prior art. Section 103 addresses obviousness—whether your invention, even if novel, would have been obvious to someone skilled in your field based on combining references. A 102 rejection means someone disclosed your invention. A 103 rejection means it’s a predictable combination of known elements.

Can I file a patent after public disclosure?

In the United States, yes—if you file within 12 months of disclosure. This is the grace period under 35 U.S.C. 102(b). Most foreign countries have no comparable grace period. Public disclosure before filing may mean permanent loss of international rights.

How far back does prior art go?

No limit. A reference from 1920 can be prior art against an application filed today, as long as it was publicly available before your effective filing date. Patents expire; the knowledge they disclosed remains prior art indefinitely.

What happens if someone else files first?

Under first-inventor-to-file, the first inventor to file generally wins. Their application becomes prior art against yours. You may still patent if your claims cover different subject matter, but for overlapping claims, the earlier filer has priority.

Does prior art have to be exactly the same as my invention?

For anticipation under Section 102, yes—a single reference must disclose every element of your claimed invention. For obviousness under Section 103, the USPTO can combine multiple references. No single reference may anticipate, but together they may render your invention obvious.

Related Resources

- Professional Patent Search Services — Find prior art before the USPTO does

- Patent Portfolio Analysis — Align IP strategy with business objectives

- Schedule a Consultation — Expert guidance on your novelty questions

References

- “America Invents Act (AIA) Frequently Asked Questions.” United States Patent and Trademark Office.

- Helsinn Healthcare S.A. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., 586 U.S. (2019).

- “MPEP Section 1120.” United States Patent and Trademark Office.

- “Provisional Application for Patent.” United States Patent and Trademark Office.

- “Inter Partes Review.” United States Patent and Trademark Office.

- “Post Grant Review.” United States Patent and Trademark Office.

This guide is provided for educational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. Patent law is complex and fact-specific. Consult a qualified patent attorney before making filing decisions.